This post primarily aims to quench my curiosities in the fastest way. Heavily reliant on my judgement and intuition.

Written from scratch by Meston Ecoa

Findings:

4. BRK sold 10% of its APPL position mid-2020, as the market was raging on after the crash from Covid. Buffet later said it was for tax reasons and regretted the decision.

How Berkshire Traded Apple

Introduction

This is me trying to rip-off investment behaviors of top funds and holding companies. Starting with Berkshire. The main aim is to see quarterly trades and try to identify commonalities in their behavior, deriving a sense of what is acceptable and what is not. These are quarterly trades, not an intra-day tradebook, but still. I remember when I was first trying out investing. I was quite lost. Now I feel that learning from the best is a good approach to start with. Fortunately sec provides a good window for the outsider.

Source: sec.gov, macrotrends

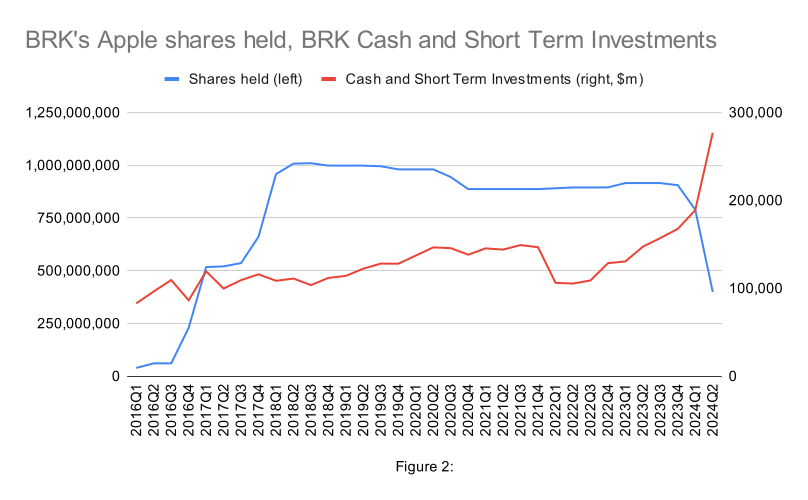

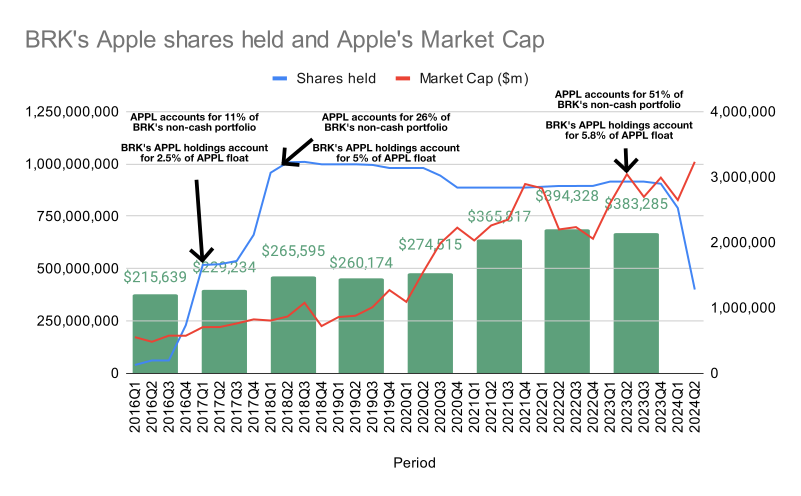

Shares held left axis

Market Cap: right axis

Green bar chart: Annual Revenue ($m)

I compiled 10 years of Berkshire’s 13F filings. With that I was able to draw their non-cash portfolio on a quarterly basis. This chart is where I want to start. Findings are as below.

• BRK bought shares aggressively from 16H2 to 18H1, a two year period. Within that two years, for the half year of 17Q2 and 17Q3, it didn’t buy much. So the piling up, really was over a 1.5year time period. Here I would like to ask him,

Q1) Why didn’t BRK buy all the shares at once in 2016?

Q2) Why didn’t they slow the accumulation in mid-2017?

• BRK aggressively piled up for 2 years, held for 6 years, and is unwinding now. Not longer than he is holding, Coca-Cola but nonetheless quite long-term indeed.

• APPL accounted for 26% of BRK’s non-cash portfolio in 18Q3. BRK didn’t really buy and sell more. It held until APPL accounted for 51% in 23Q2. Warren Buffet really meant it when he said he doesn’t believe in diversifying. His stock portfolio is almost invariably around 40 stocks at any given moment. Depending on the comparison it could be a lot, or could be very little. However, it’s hard to believe that a multi-billion dollar holding company let one stock take up half the non-cash portfolio. (Yes, yes, their size is too big to wager on small-sized opportunities but still.) This gives me implications as an individual investor.

• BRK didn’t buy more shares in any meaningful amount, but APPL’s float continuously decreased, making BRK’s shares more valuable.

• BRK sold 10% of its APPL position mid-2020, as the market was raging on after the crash from Covid. Buffet later said he regrets the decision.

• BRK didn’t buy nor sell throughout 2021. The market was really good in 2021 all around.

• BRK bought the dip in 2022 just a little bit. Increased APPL shares holdings by 3%.

Source: sec.gov, Gurufocus, Macromicro

The video is from 2023 annual shareholder meeting. He says “Apple is a better business than any other we own.” Then I got curious. I want to check all the times Warren Buffet mentioned “Apple” in all the previous annual shareholder meetings. I’ve listed them below. These transcripts are from cnbc. I recommend skipping to the summary.

Q: “Warren, for years, you stayed away from technology companies, saying they were too hard to predict and didn’t have moats. Then you seemed to change your view about technology when you invested in IBM, and again when you recently invested in Apple. But then on Friday you said IBM had not met your expectations and sold a third of our stake. Do you view IBM and Apple differently? And what have you learned about investing in technology companies?”

A: “Apple — I regard them as being in quite different businesses. I think Apple is much more of a consumer products business, in terms of the — in terms of sort of analyzing moats around it, and consumer behavior, and all that sort of thing. It’s obviously a product with all kinds of tech built into it. But in terms of laying out what their prospective customers will do in the future, as opposed to, say, IBM’s customers, it’s a different sort of analysis.”

WARREN BUFFET: And, then, fairly recently, we took a large position in Apple, which I do regard as more a consumer goods company, in terms of certain economic characteristics. Although, that —

You know, it has a huge tech component in terms of what that product can do, or what other people might come along to do, to leapfrog it in some way.

CHARLIE MUNGER: I think it’s a very good sign that you bought the Apple. It shows either one of two things. Either it is you’ve gone crazy or you’re learning. (Laughter) I prefer the learning explanation.

WARREN BUFFETT: Well, so do I, actually. (Laughter)

Q: “And given your sometimes critical views on buybacks, do you think Apple would do better spending a hundred billion dollars on buybacks, or buying other productive businesses the way you have generally preferred? A hundred billion dollars is a lot of money.”

A: “Because I think it’s extremely hard to find acquisitions that would be accretive to Apple that would be in the 50 or 100 billion, or $200 billion range. They do a lot of small acquisitions. … And, you know, I’m delighted to see them repurchasing shares. We own — let’s say we own 250 million or so shares. They have, I think, 4 billion, 923 million or something like that. And mentally, you can say we own 5 percent of it. … But I figure with, you know, with the passage of a little time we may own 6 or 7 percent simply because they repurchase shares. And it — I find that if you’ve got an extraordinary product, and ecosystem, and there’s lots to be done, I love the idea of having our 5 percent, or whatever it may be, grow to 6 or 7 percent without us laying out a dime. I mean, it’s worked for us in many other situations. But you have to have some very, very, very special product, and — which has an enormous wide — enormously widespread ecosystem, and the product’s extremely sticky, and all of that sort of thing. And they’re not going to find 50 or a hundred billion dollar acquisitions that they can make at remotely a sensible price that really become additive to that.

“You know, you have to look at — See’s Candy, you know, if you live in California and you were a teenage boy, and you went to your girlfriend’s house and you gave the box of candy to her or to her mother or father and she kissed you, you know, you lose price sensitivity at that point. (Laughter) So we really want products where people feel like kissing you, you know — (laughs) — rather than slapping you. It’s an interesting thing. I mean, you know, in effect we’re betting on the ecosystem of Apple products, but — led by the iPhone. And I see characteristics in that that make me think that it’s extraordinary. But I may be wrong.”

“And I didn’t go into Apple because it was a tech stock in the least. I mean, I went into Apple because I made certain — came to certain conclusions about both the intelligence with which the capital would be employed, but more important, about the value of an ecosystem and how permanent that ecosystem could be, and what the threats were to it, and a whole bunch of things. And that didn’t — I don’t think that required me to, you know, take apart an iPhone or something and figure out what all the components were or anything. It’s much more the nature of consumer behavior. And some things strike me as having a lot more permanence than others.”

Q: “Given that Apple is now our largest holding, tell us more about your thinking. What do you think about the regulatory challenges the company faces, for example? Spotify has filed a complaint against Apple in Europe on antitrust grounds. Elizabeth Warren has proposed ending Apple’s control over the App Store, which would impact the company’s strategy to increase its services businesses. Are these criticisms fair?”

A: “Well, again, I will tell you that all of the points you’ve made I’m aware of, and I like our Apple holdings very much. I mean, it is our largest holdings. And actually, what hurts, in the case of Apple, is that the stock has gone up. You know, we’d much rather have the stock — and I’m not proposing anything be done about it — but we’d much rather have the stock at a lower price so we could buy more stock.”

“We owned — I mentioned and used Apple as an example of how our interest in Apple, you know — every time a company that earns a hundred billion a year — you know — it means that our interest in it goes up a tenth of a percent. You know, we’ve added another a hundred million to earnings. And we actually bought a little more Apple, in the first quarter or so.We decided we wanted to own a greater interest. And on top of that, we knew that we would own an even greater interest if they kept buying in their shares, which — we didn’t have any insider information or anything — but certainly, it would seem the way to bet.”

It’s been good for Apple and good for China. That’s the kind of business we ought to be doing with China. And more of it. Everything that increases the tension between the two countries is stupid, stupid, stupid. It ought to be stopped on each side. And each side ought to respond to the other side’s stupidity with reciprocal kindness. That’s my view.

Q “Looking at the global trends, it increasingly does seem that zero-emission vehicles may have finally reached the cusp of mass adoption. Do you see any opportunities in this space, either in specific vehicle manufacturers or in related technologies?”

A: “But I think I know where Apple’s going to be in five or ten years, and I don’t know where the car companies are going to be in five or ten years. And I may be wrong. But Charlie and I follow the auto business with intense interest. Charlie’s firm was the specialist at General Motors on the Pacific Coast Stock Exchange, and that was a franchise, wasn’t it.”

Q: “During an episode of Investing the Templeton Way podcast, Professor Damodaran, who he respects almost as much as Warren and Charlie, mentioned that he is not comfortable with positions becoming a large part of his portfolio. For example, when they reach 25-35%. He mentioned that Apple is now 35% of Berkshire’s portfolio and thinks that that is near a danger zone.” Wonders if Warren and Charlie can comment.”

A: “CHARLIE MUNGER: I think he’s out of his mind.

WARREN BUFFETT: Yeah, I knew that was coming. (Laughter) Apple is not 35% of Berkshire’s portfolio. Berkshire’s portfolio includes the railroad, the energy business, Garanimals, you name it, See’s Candies, they’re all businesses. And, you know, the good thing about Apple is that we can go up.They buy in their stock, and instead of owning 5.6%, they got about 15 billion, 700 and some million shares outstanding. They get down to 15 and a quarter billion without us doing anything. We got 6%. So, we can’t own more than 100% of the BNSF. We can’t own more than 100% of Garanimals or See’s Candies. And it would be nice. We’d love to own 200%, but it just isn’t doable. But they’re all the same. They’re good businesses. And to think that our criteria for Apple is different than the other businesses we own, it just happens to be a better business than any we own. And we put a fair amount of money in it, but we haven’t got more money in it than we’ve got in the railroad. And Apple is a better business.Our railroad is a very good business. But it’s not remotely as good as Apple’s business. Apple, you know, has a position with consumers where they’re paying, you know, maybe the $1,500 bucks or whatever it may be for a phone. And these same people pay $35,000 for having a second car. And if they had to give up a second car or give up their iPhone, they’d give up their second car. I mean, it’s an extraordinary product. We don’t have anything like that that we own 100% of. But we’re very, very, very happy to have 5.6%, or whatever it may be, and we’re delighted every tenth of a percent that goes up. That’s like adding $100 million to our share of the earnings. And they use the earnings to buy out our partners, which we’re glad to see them sell out, too. The index funds have to sell if they (Laugh) bring the number of shares down. And, you know, we went up slightly last year, and I made a mistake a couple years ago when I sold some shares when I had certain reasons why gains were useful to take that year from a tax standpoint. But having heard me say that, it was a dumb decision. (Laugh) And, Charlie, you’ve already given your comment about it. But we do not have 35% of Berkshire’s portfolio. Berkshire’s portfolio is the funds we have to work with. And we want to own good businesses. And we also want to have plenty of liquidity. And beyond that, you know, the sky’s the limit or our mistakes. Who knows what the bottom is?

Q: “It shows that Berkshire sold another 115 million shares of Apple in this last quarter. … Have you or your investment managers’ views of the economics of Apple’s business or its attractiveness as an investment changed since Berkshire first invested in 2016?”

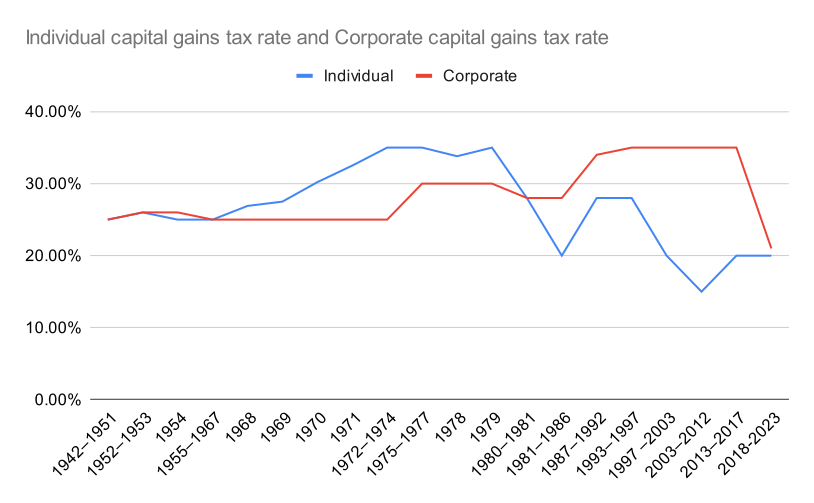

A: “Almost everybody I know pays a lot more attention to not paying taxes, and I think they should. We don’t mind paying taxes at Berkshire, and we are paying a 21% federal rate on the gains we’re taking in Apple. And that rate was 35% not that long ago, and it’s been 52% in the past when I’ve been operating. And the government owns… The federal government owns a part of the earnings of the business we make. They don’t own the assets, but they own a percentage of the earnings, and they can change that percentage any year. … And the percentage that they’ve decreed currently is 21%. And I would say, with the present fiscal policies, I think that something has to give, and I think that higher taxes are quite likely, and if the government wants to take a greater share of your income, or mine or Berkshire’s, they can do it. And they may decide that someday they don’t want the fiscal deficit to be this large, because that has some important consequences, and they may not want to decrease spending a lot, and they may decide they’ll take a larger percentage of what we earn, and we’ll pay it.

From the annual shareholder meeting talks of Apple. Certain points are apparently repeated.

• They view Apple’s strength in a consumer behavior perspective, not a techincal moat perspective.

• They are comfortable taking huge positions in Apple

• They are happy with the stock repurchases (as with any other companies that do that) bringing up their holdings from 5% to 6%, give that they buy at a fair price.

• He said in 2023 that he made a mistake a a couple years ago selling shares. Back then he sold it in a tax standpoint.

• He hints in 2024 that he sold Apple to use the “low” corporate capital gains tax of 21%, and expects it to go up to handle deficit.

Source: wolterskluwer

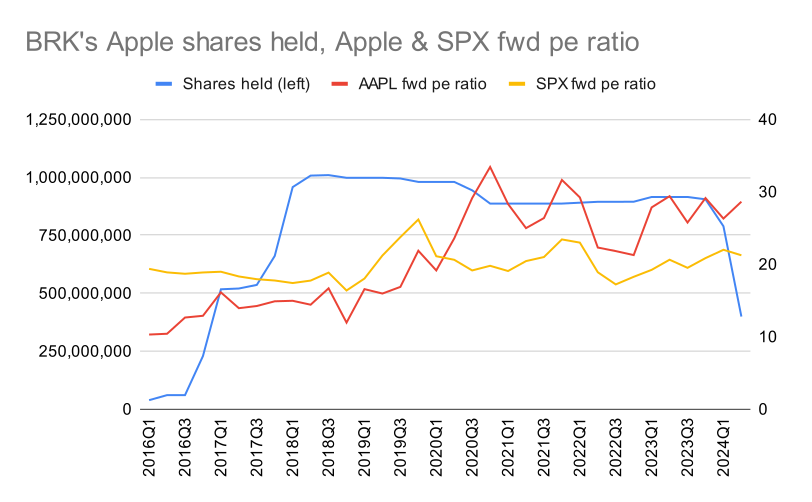

He repeats the importance of thinking about the business, not the market. Market is there to serve you, and the only reason to observe markets is to see if it provides good opportunities. But it doesn’t mean he doesn’t see the macro, and the economy. He would, in fact, do that. Did Warren Buffet really sell Apple because he doesn’t believe in the company anymore?

Warren Buffet doesn’t strike me as the guy that sells because it would underperform the market. There’s plenty of investments like Coca-cola that has underperformed the market. He held it for a long time. My guess is that he is really concerned about recession and the current debt levels. He would rather play safe and have cash. Also his interest in energy shows that energy is really the next big thing. I think his narrative would be that with EV and data centers, electricity usage growth is apparent and energy is something that he understands. Tax would have something to do with it. He is all for saving taxes. Well he is all for maximizing shareholder value, which then you would have to save taxes.

Written from scratch by Meston Ecoa

May contain incorrect data and information